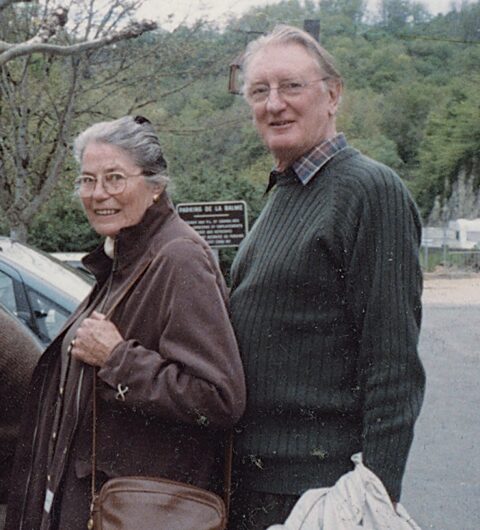

Peter was our friend. He was part of the furniture here for longer than most of us can remember.

Not only as a diligent member and supporter of the Guild of St Bride and as Treasurer of the PCC for many years. Not only in his work for the St Bride’s Foundation. Not only as a faithful and regular congregant. But also as a man who forged personal friendships with a wide variety of people he found here, and who gave more and more time and energy to those relationships beyond the sad death of his beloved wife Jean.

John Oates was Rector here during the 1980s when the Longlands first arrived, lured over Blackfriars Bridge by choruses wafting from here and almost through the open windows of their apartment overlooking the River Thames.

‘They were a very interesting couple,’ remembers John. ‘When they joined us, Peter was already retired. We got to know them socially, though he kept himself to himself. One never knew a great deal about his family life, or his private affairs. When I retired, Peter would visit me in Kingston. We valued him greatly.’

John’s successor, David Meara, who was Rector of St Bride’s from 2000 until 2014, remembers Peter and Jean as ‘stalwart members of the church, and great supporters of its musical tradition. They both loved to travel. They were patrons of the English National Opera, and often took Rosemary and me to their box, before dinner afterwards at their favourite restaurant, in Waterloo. Peter was immensely generous, and full of curiosity about the world.’

Janet and Terence Smith, former Sunday School leader and Electoral Roll manager and Guild Marshall respectively, describe Peter as ‘a gentle man – in every sense of the word. He was kind and caring, and had time to speak to everyone. Peter joined the Guild of St Bride in 1992, and served faithfully every Sunday, mainly on Usher duty. He had high expectations of himself, and his welcoming skills were greatly appreciated. His interests outside the church were painting, theatre, music and travel. He loved cruises. He had recently returned from a cruise in Europe, and was planning another to Antarctica this coming June.’

Peter Silver, a former churchwarden here, recalls ‘a very astute man. A dear confidant. We worked closely together when he was Chair of the St Bride’s Foundation Board of Trustees. He drew me into their number, eventually recommending me as his own successor. His wise counsel and great friendship will be much missed.’

Alison Lee, St Bride’s Foundation manager, found Peter incredibly supportive, both as chair and as emeritus president. ‘He helped me hugely,’ she says. ‘But the thing I will always remember and be grateful for is the friendship we established over regular coffees, discussing everything from art and theatre to travel and the latest technology updates. There was always a lot of laughter. I can hear him laughing when I think of him now.’

Gabriele Fyjis-Walker was another of Peter’s regular opera partners. She remembers many memorable evenings at Covent Garden, during which he would smile throughout. ‘Conversation over dinner always offered me informed insights into the music and productions,’ she recalls, ‘as he was a true connoisseur. We also exchanged news, views and memories of Sudan. We had both lived in that remote desert country, Peter much earlier than my diplomat husband and I. As very little had changed in the Sudanese way of life between the 1960s and the 1980s, we were able to share our mutual liking for its people. Living in the desert with the Nile as the only source of water, no hint of spring, autumn or winter skies but just hot and very hot days, and an acceptance of the Arabic word mafi, There Is Not, meant that we learned to live without electricity, petrol, eggs or any variety of food for much of the year. This, we agreed, had been a formative and very positive experience.’

Daily deprivation clearly imbued Peter with an appreciation of abundance.

Mary Walker, the Longlands’ close friend and neighbour for years, recalls that, whenever you asked Peter a question about something, he would give a considered opinion. ‘A very considered opinion.’

Oh, yes. That was Peter. A man of measure, wisdom and immense humour, who adored double entendre, a little wordplay and a juicy pun. A dignified gentleman, precise, impeccably-dressed and -mannered. Elegant and worldly. He walked easily alongside people of every faith and from all walks of life. He never judged others. He regarded negatives as positives, in that they afford opportunities to restart or to improve. ‘You are not your past,’ he once said to me. ‘It is never too late to become the person you’ve always wanted to be.’

There was a sense that Peter was reinventing himself all the time, even into his nineties. He returned to his painting with gusto after he was widowed, and was delighted to exhibit his work. Nor was his love of music confined to classical, choral and opera. After reading an extract of my showbusiness and music journalism memoir in The Times, he purchased the book, read it, and invited me to lunch.

‘I need you for something,’ he said. ‘All those years that I spent in far-flung countries meant that the cultural revolution of the 1960s and ’70s passed me by. I know nothing about the Beatles or the Rolling Stones and the reSt I’m not saying I will like their music, necessarily. I’m keeping an open mind. But I am not proud of the yawning gaps in my knowledge. Will you teach me?’

There ensued lunches.

Peter had friends in high places. Sometimes literally. Once, when I was about to travel to Umbria, he emailed, ‘Give my regards to Perugia, would you? I know it reasonably well. A friend and his wife own the Castello in nearby Gubbio. His Italian great-great-grandfather was a leader in the Risorgimento, and received the ancient monument as a reward. I’ve stayed there many times. It must be one of the highest, coldest and most draughty places I have ever attempted to sleep in. But what should one expect of a castle teetering on the top of a rocky outcrop, its foundations all but flapping in the wind?

When I sent him the press release for my book about the Rolling Stones, he emailed back immediately:

‘Yet again, I am to be treated to subjects and people of which I have very little knowledge, let alone experience,’ he enthused. ‘Travel may broaden the mind, but it also fragments one’s life. I look forward to devouring this book during my cruise back to Norway, and to becoming as Stoned as the rest of the world.’

When my younger two children were little, they didn’t know Peter’s name. They called him ‘Please Wait’ – referring to his habit of articulating those words when controlling the crowds of congregants stampeding towards the altar rail to receive Holy Communion. I told him about this years later. He had the grace to laugh like a drain.

Thank you, dear Peter, and God bless you.